Crop Insurance

Farming is a high-stakes business where weather, pests, and markets can swing a season from profit to loss.

Crop insurance helps agricultural producers steady that ride by transferring a portion of risk to insurers. It’s a practical risk management tool – used before, during, and after the growing season.

Crop Insurance Explained

Crop insurance is a set of crop insurance policies that protect crop production and/or farm revenue against specified causes of loss – think drought, flood, hail, freeze, disease, or sharp price drops.

In the United States, most coverage is delivered through the federal crop insurance program: private insurance companies providing crop insurance to farmers, with premiums partially subsidized and policies standardized by the government (often referred to as federal crop insurance).

Similar public–private crop insurance programs exist in many other countries. In day-to-day terms, crop insurance coverage is selected on insured “farm units” (individual fields, basic/optional units, or combined enterprise units), with the farmer choosing coverage levels and options that match their risk tolerance and budget.

How Does Crop Insurance Work?

At the start of a season, a producer selects a crop insurance policy (e.g., yield or revenue), defines the farm units to be insured, and chooses a coverage level—say 70% or 80% of expected crop production or revenue.

Premiums are calculated on those choices; in a federal crop insurance program, a portion is typically subsidized.

If a covered peril strikes during the growing season—natural disasters like drought or flood, or a market price collapse—the farmer files a claim. Adjusters verify yields or revenue, compare actuals to the insured guarantee, and pay an indemnity for the shortfall.

Example: An Iowa corn grower insures an enterprise unit at 75% revenue coverage.

Expected revenue is €1,000 per hectare.

A dry summer cuts yields and harvest-time prices also fall, dropping actual revenue to €650 per hectare.

Because the insured guarantee is €750 (75% of €1,000), the policy pays €100 per hectare to close part of the gap.

Why do farmers buy crop insurance?

For most farm businesses, crop insurance is one of the essential risk management tools that keeps operations resilient through volatile seasons.

- Income stability: Protects cash flow when natural disasters or market swings reduce yields or prices, smoothing year-to-year income.

- Access to capital: Lenders often view insured operations as lower risk, so coverage can support financing for seed, inputs, and equipment.

- Operational confidence: With a crop insurance program in place, producers can plan rotations, invest in technology, and scale farm units knowing a safety net exists if the growing season goes sideways.

Brief History of Crop Insurance

In the United States—the most mature and robust crop insurance market—the program’s roots stretch back many decades.

The federal government created the Federal Crop Insurance Corporation (FCIC) in 1938 to pilot a national safety net for farmers after the Dust Bowl.

For decades it remained small.

The turning point came with the Federal Crop Insurance Act of 1980, which expanded the program nationwide, introduced meaningful premium subsidies, and brought private insurers into distribution and servicing as approved insurance providers (AIPs). That’s when crop insurance began operating at scale.

In the 1990s and 2000s, Congress refined the framework so it could function as a key federal support program rather than a disaster-by-disaster fix. The 1994 reforms added basic catastrophic (CAT) coverage and higher subsidies to encourage participation; the 2000 enhancements pushed adoption further and broadened coverage options to include revenue-based guarantees. Subsequent Farm Bills streamlined administration, strengthened actuarial soundness, and promoted options like Whole-Farm Revenue Protection—extending crop insurance beyond single crops to what are essentially whole farm units for diversified operations.

Operationally, the FCIC sets policy terms and reinsures risk; the USDA’s Risk Management Agency administers the rules; and approved insurance providers (the private insurers) market, underwrite, and adjust crop insurance policies.

Farmers select coverage, pay their share of premium (reduced by premium subsidies), and receive indemnity payments when actual yields or revenues fall below the insured guarantee. This shared structure aligns scale (national pooling and federal backstop) with local execution (agents and adjusters who understand regional production realities).

Outside the U.S., many countries run analogous public–private arrangements—often with targeted subsidies, standardized products, and reinsurance support—yet the U.S. model remains one of the most mature, with the breadth of coverage options, extensive data, and a deep network of approved insurance providers making federal crop insurance a cornerstone of American farm risk management.

Types of Crop Insurance

In the U.S., most crop insurance is delivered through the federal crop insurance program, which standardizes products and pricing while letting farmers choose from practical coverage options.

At a high level, growers encounter three families of crop insurance policies: multiple peril crop insurance (MPCI), crop-hail, and revenue products. Below we start with MPCI, the backbone of most federal crop insurance policies administered by USDA’s Risk Management Agency (RMA) and sold by private carriers.

Multiple Peril Crop Insurance (MPCI) Policy

Multiple peril crop insurance (MPCI)—sometimes written multiperil crop insurance or multi peril crop insurance—protects against a broad list of natural perils that threaten crop production (e.g., drought, excess moisture, flood, freeze, disease, pests). Under the federal crop insurance program, MPCI forms are standardized nationwide; the Risk Management Agency (RMA) sets rules, rates, and actuarial standards, while approved insurance providers and agents deliver the policies locally. State-level consumer protections and licensing still apply—state insurance departments oversee sales practices—even though terms are federal.

Crop-Hail Insurance

Crop-hail insurance is a private, named-peril product sold outside the federal crop insurance program.

It’s often used alongside MPCI or revenue plans to fill a very specific gap: localized hail damage that can shred leaves or bruise fruit without pushing the farm’s overall yield low enough to trigger an MPCI indemnity.

Policies are highly customizable—growers can insure specific fields, choose deductibles (or “percentage-of-loss” plans), and add options that may include fire, lightning, vandalism, or even transit coverage, depending on the state. Because crop-hail insurance is not federally subsidized, rates and forms vary by carrier and state; oversight comes from state insurance departments, and claims are paid based on the adjuster’s measured percent damage multiplied by the insured value. In short, this is crop insurance that pays quickly for spot losses and complements broader crop insurance policies.

Crop Revenue Insurance

Crop revenue insurance protects both yield and price, guaranteeing a minimum level of revenue rather than just bushels.

Within the federal crop insurance program, the flagship offerings are Revenue Protection (RP), RP with Harvest Price Exclusion (RPHPE), and area-based revenue plans. The guarantee is typically calculated as: approved yield × chosen coverage level × a projected price set by USDA/RMA methods. If actual revenue (actual yield × harvest price) falls below that guarantee, the policy pays an indemnity.

With RP, the guarantee can rise if the harvest price ends up higher than the projected price—useful in drought years when yields fall and prices spike.

Because these are federal crop insurance policies, they come with premium subsidies and standardized terms delivered by approved insurers and agents.

Farmers who market grain ahead of harvest or face significant price volatility often prefer crop revenue insurance to simple yield protection, since it aligns crop insurance with real-world income risk.

How much does crop insurance cost?

For most agricultural producers, the cost of crop insurance is built from an actuarial base and then reduced by federal support. In the U.S., the Federal Crop Insurance Corporation (FCIC) (administered by USDA’s RMA) sets the rules and provides reinsurance, while approved insurance providers sell and service crop insurance policies locally. In short: Washington designs the framework; private carriers deliver it; producers choose coverage and pay their share.

At its core, a crop insurance premium is tied to the size of your guarantee (liability) and the risk where you farm. Liability reflects approved yield or revenue, your elected coverage level, projected price, and your insurable share—which is based on land and crop ownership (your “share” as owner, operator, tenant, or sharecropper).

What you actually pay is your farmer-paid crop insurance premium after premium subsidies.

Following 2025 updates, according to USDA subsidy rates for most individual (farm-level) crop insurance plans are: Optional/Basic Units—67–69% subsidy at 50–60% coverage, moving down to 41% at 85%; Enterprise Units—80% subsidy from 50–75% coverage (71% at 80%, 56% at 85%). In addition, area add-ons like SCO and ECO now receive 80% subsidy.

These changes were implemented by RMA in August 2025 and apply as policies roll forward.

Beyond the premium itself, there are standard fees.

For “buy-up” levels (anything above CAT), there’s a $30 administrative fee per crop per county; for CAT coverage, the fee is $655 per crop per county.

Beginning farmers and some underserved categories can qualify for fee waivers and extra premium support; RMA’s 2025 update further enhanced Beginning Farmer and Rancher benefits. These items affect your out-of-pocket crop insurance premium even though they don’t change the underlying actuarial rate.

Crop Insurance: Specialty Insurance Line

Crop insurance sits squarely in specialty insurance.

It looks nothing like personal auto or standard commercial property: underwriting hinges on biology, weather, and markets—plus the unique structure of the U.S. public–private system.

Policies follow the rhythm of planting, acreage reporting, and harvest; losses cluster around regional weather events; and indemnities often reflect both agronomic outcomes and price movements.

The result is a niche where expertise, timing, and data quality matter as much as capital.

Given those realities, technology is a competitive edge. Specialty carriers benefit from a nimble rating engine, a policy administration system that understands crop-specific workflows, strong data ingestion (satellite, weather, USDA/RMA publications), and analytics that surface exposure hot spots before a storm hits.

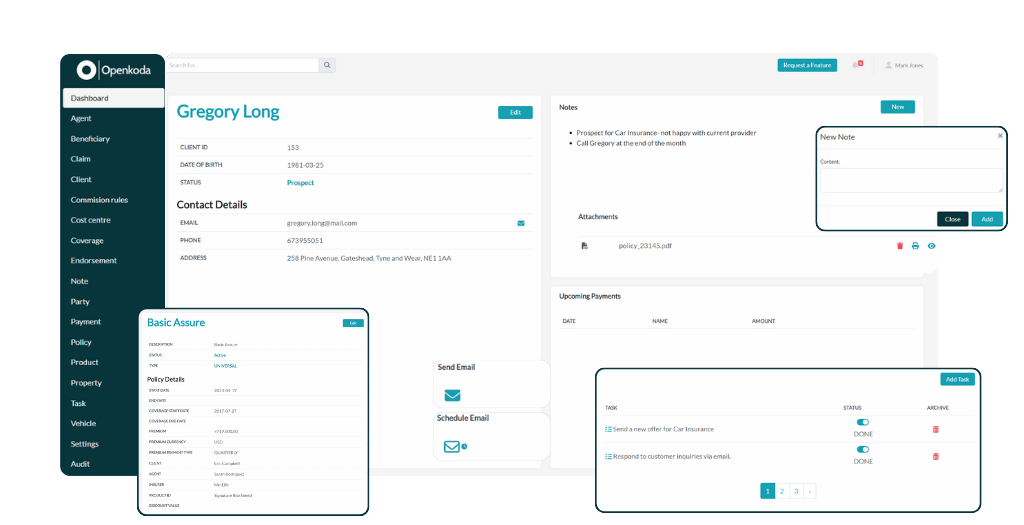

If you’re building or modernizing this stack, platforms like Openkoda can help teams quickly assemble custom software for specialty lines—integrating submissions, rating, policy administration, and claims dashboards—without locking you into rigid off-the-shelf templates.

Openkoda’s modular architecture lets you model crop-specific entities—farm units, APH histories, and prevented planting—and still keep RMA compliance rules codified and testable. Its open-source core exposes clean APIs for ingesting satellite/weather data and supports bulk workflows for acreage and production reporting, so operations keep pace with the season.

And because there’s no vendor lock-in, you can deploy on your cloud, keep your data governance intact, and evolve the platform as your crop insurance portfolio changes.

Closing Thoughts

Crop insurance is, at its core, a practical safety net that turns unpredictable weather and markets into more manageable business risk.

The strongest results come from matching coverage—MPCI, hail, and revenue options—to your crop mix, unit structure, and cash-flow needs, then revisiting those choices as prices, practices, and regulations evolve.

Work with an experienced agent, lean on RMA resources, and treat each renewal as a chance to fine-tune your risk strategy for the next growing season.